For all those who are interested, the complete rules for Faerie Tales & Folklore can be downloaded in a convenient PDF format through the link below (click on the image, the link will take you to DriveThruRPG). This link will be updated along with the game and the rules are free to use for the purposes of play or personal reading. If you enjoy the material, please leave a comment and keep on the lookout for the coming KickStarter!

Archetypes, Talents, and the Evolution of Character

After an interesting conversation in a chat room on MeWe, I came to realize that it was time to publish an article on one of the most important ways any given character may differentiate themselves within Faerie Tales & Folklore… Talents. I have written at length about class, lineage, the introduction line, magic, and many other aspects of the game in general. However, I never really delved into talents and how they were intended to be used within the world of the Mythological Earth. I hope to remedy this situation by using talents, along with other character choices, to build some of the most iconic class archetypes from the earliest editions of Dungeons & Dragons.

This article will be similar to my article “I’ve a Feeling We’re Not in Kansas Anymore”, in that it is an exploration of how the various subsystems in Faerie Tales & Folklore can be used in ways that might not be readily apparent. The Mythological Earth and the rules that support it are vast, sometimes a little insight into how those rules bring ideas to life are just the sort of tale a player or narrator needs to hear. With only three lineages, three classes, and a handful of professions, it can seem if some truly loved ideas must have been cast to the cutting room floor. However, this has not been the case. In the following paragraphs, I hope to state my case.

First let us get some page references out of the way to make this process easier to follow.

- The three available lineages are discussed on pages 25-37.

- The three available classes are detailed on pages 38-50.

- The twelve professions are briefly discussed on pages 59-62.

- Talents are covered on pages 70-75.

In addition to these basic references, it is also important to take a look at the idea of the “introduction line” on page 66, and the various archetypes offered on 625-633. All of this information aids in both understanding and utilizing the concepts offered in this article. It is probably a good idea to have at least a basic understanding of both the magic and combat systems, as many of the talents that will be mentioned below directly relate to either system and how they function. Now that the boring stuff is out of the way, let’s wade into the fun stuff…

The Assassin (Hashīshiyyīn, Shinobi-No-Mono or Thuggee)

To begin, I will attempt to recreate the assassin, inspired by the hashīshiyyīn told of in Marco Polo’s writings. These highly trained killers were religious warriors who used guerrilla tactics and terror to improve their odds of victory. Though this build is intended to recreate an individual of a specific culture and place in history, it makes a good basis for other zealous killers of history (such as the Shinobi-No-Mono or the Thuggee)

The lineage which best fits such a character is that of common men. It is the strong religious predilection of common men which makes them a near perfect fit. Add to this the ability to call upon deified spirits for miracles and drive off spirits fits well with the idea of a holy guerrilla warrior. The obvious choice for class is a sneak-thief. The skill set offered by this class is essential to creating an effective killer. As for profession, an assassin can come from any line of work or social standing, so this choice is free to use for color and customization.

Let’s now look at the talents which complete this build, listed from the least to the most costly.

- Pugilist (basic talent): It is important for most trained killers to be lethal no matter the situation they find themselves in.

- Swiftness (basic talent): Mobility is of paramount importance for the effective use of guerrilla tactics.

- Knack (standard talent): Many assassins take to the study of alchemy or chemistry in the attempt to learn more about poisons and under useful substances to aid in their goals. This talent offers a simple way to acquire such skills outside of profession.

- Militia (standard talent): The option of taking berserkr fits extremely well here. It is a shoe in for the “I complete my job or die trying” mentality. This option can also be a good substitute for a lack of armor.

- Training (standard talent): Understanding the proper use of a great many weapons is of a clear advantage to a dyed in the wool killer.

- Warrior (standard talent): Traditionally, the hashīshiyyīn eschewed using missile weapons, instead opting to focus on melee combat. This talent is also a prerequisite for specialization, a talent that is central to the build.

- Evade (expert talent): Being able to avoid detection until the moment of the strike and than vanish again before anyone knows what has happened, is the desire of most assassins. This talent can help realize such a goal.

- Specialization (mastery talent): Critical hits are an important portion of an assassins combat style. This talent ensures there will be a greater number of critical hits.

- Watchful (mastery talent): Being surprised is a death sentence for an assassin, being immune to surprise helps a bit.

This assassin build fills the more traditional descriptions of these often misunderstood killers. Though not strong in supernatural ability, this assassin is a cunning, efficient dealer of death. This is the thinking man’s warrior, the one who uses every available advantage to ensure the completion of their objectives. (Continued below)

The Bard (Rú, Shaman, or Skáld,)

This archetype is both loathed and loved, again with roots that go way back into the history of D&D. This is the true tabletop jack-of-all trades, a learned warrior who also wields the full might of magic. The bard, and other shamanic musicians, use music as a channel for the conjuration of otherworldly forces. These folks are often skilled in the arts of warfare as well as the history and mythology of their culture. Bards are the ones who tell the stories, it is they who shape how we remember and what we remember. Many, such as the shaman or rú, hold an almost religious significance among the people with whom they reside.

A bard is a complex archetype, with many possible variations on the theme. As such, defining the bard is going to be a bit involved. The lineage which best suits this archetype is that of a multi-class high man. This means that the class of the build is two fold, fighting-man and magic-user. This offers a plethora of abilities which make for a highly flexible and interesting role to play. The best profession for such a build is the variation of the traveling entertainer known as the bardd (page 540). As it offers the stronger position within the community.

A bard is likely to purchase a wide array of talents in support of their already vast skill set, though knowledge and leadership are commonly at the forefront.

- Swiftness (basic talent): Discretion is the better part of valor.

- Accurate (standard talent): This talent can be seen as optional, but should be taken if there is a greater desire for martial prowess.

- Knack (standard talent): A bard is likely to know at least one unusual skill of worth. Their worldly nature almost forces it.

- Legerdemain (standard talent): The enterprising bard can use subtle tricks to make a performance more memorable, make simple changes to their appearance, and other useful but relatively minor bits of magic.

- Militia (standard talent): The abilities of both commander and duelist are useful to the bard, and both can be had with his talent and the class of fighting-man.

- Warrior (standard talent): As with accurate (above), this talent affords improved combat prowess. Though handy, this remains an optional choice.

- Attribute (expert talent): A bard needs a better set of attributes than most to truly exemplify their role. This talent can and most often will be taken up to three times.

- Leaned (expert talent): A bard commonly possess a great deal of worldly knowledge.

- Natural (expert talent): This talent is very useful to all practitioners of the magical arts.

- Sharpshooter (expert talent): Many members of this “jack-of-all-trades” possess a frightening skill at weapons of all types, especially missile weapons. Nothing like an “impossible shot” to woo an audience.

- Gifted (mastery talent): An additional known spell is invaluable.

- Leader (mastery talent): This talent solidifies the bard as a voice of their community.

- Specialization (mastery talent): For those bards who have committed much to the art of war, this talent is the cap stone. In simple terms, critical hits finish fights quickly, and often with a dramatic flair.

In its bare unadorned form, this version of the bard, is the classic fighter/magic-user of many settings. With this build, true military might has been overshadowed by education and magical studies, but they are nonetheless capable on the battlefield. The bard, shaman, or skáld is a valued member of any community and, in places where the archetype flourishes, they often fill advisory roles to the leaders themselves. The additional options offered in this build’s talents create a truly formidable and well rounded character, by giving a strong boost to the archetypes combat abilities. It is worth noting that the amount of experience required to complete the more combat capable version of this build is a staggering sum. (Continued below)

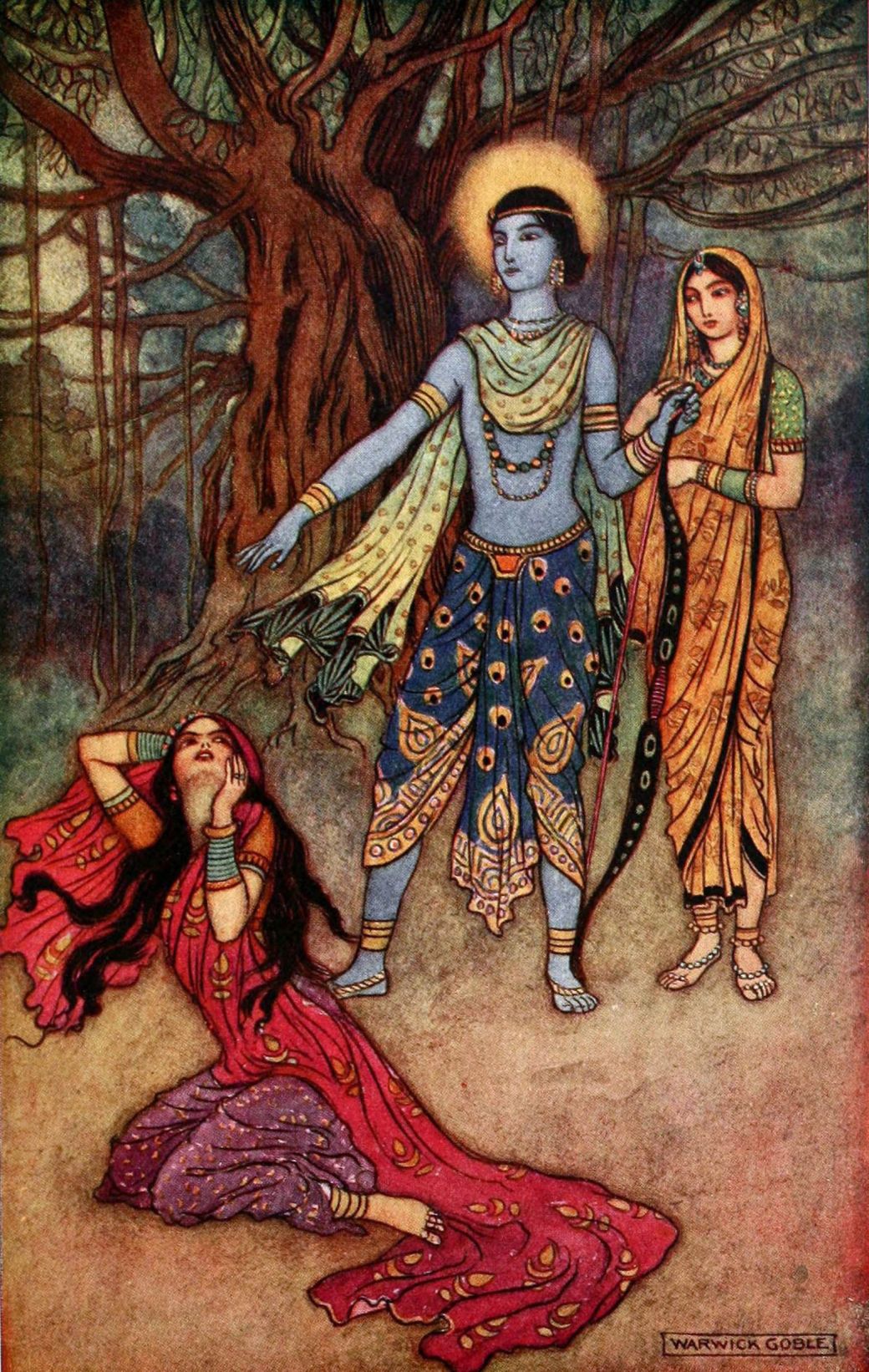

The Cleric (Brahmin, Drui, or Paladin)

This archetype is a game table favorite almost everywhere, and for good reason. The cleric offers a decent midway point between a pure fighting-man and a magic-user. Recreating this archetype is a bit more difficult than some other archetypes, but in the end it offers more of the feel of a religious warrior. The cleric is often the spiritual voice of the community of which they are part, or at least one such voice. However, they are often the ones who ate first to rattle the sabers of war. Though the cleric is often seen in through the lens of Christianity, this build would suffice for the Hindu Brahmin, the Gael Drui, or a Magus of Mazdayasna.

The choice of lineage is also rather easy in this instance, it can only be a common man. Religion is almost exclusively practiced by common men within the Mythological Earth, thus the priesthood is most likely to be composed entirely of common men. As for class, it is a fighting-man which seems the best choice. Not only does this create a resilient warrior, but it allows for the lands and armies to further the territory of one’s beliefs. As for profession, ordained priest is the natural choice.

- Resistant (basic talent): It is more common for the religious zealot to find themselves facing all manner of otherworldly foe and the threats they bring to bear. This talent can help with the sting a bit.

- Hardened (standard talent): This talent can offer a good explanation for the mythical will of the faithful.

- Knack (standard talent): Most members of a priesthood are well educated for the era in which they live. This talent can be used to acquire many important skills which are often associated with the priesthood (such as chirurgery or herbalism).

- Militia (standard talent): Between the choice provided as fighting-men and that of this talent, the cleric may gain two of these important abilities. Of those available, berserkr can offer the feel of divine fury, while commander can improve the already impressive leadership abilities of fighting-men.

- Stamina (standard talent): This furthers the tireless will of the divinely driven.

- Learned (expert talent): As discussed previously, those of the priesthood regularly enjoy a much greater level of education.

- Tireless (expert talent): The will to persevere.

- Blessed (mastery talent): Divinely inspired heroes must face the most foul of foes. This talent helps ensure the cleric is equipped to face all manner of supernatural evils and should likely be taken twice.

- Leader (mastery talent): This truly caps the strength of the clerics leadership skills. At this point they can command large numbers of the faithful to meet threats of unimaginable horror.

This recreation of the old favorite gives a more grounded representation of the battle ready religious acolyte then some more “traditional” takes in TTRPGs, however, this cleric offers all the meat and potatoes required: leadership, miracles, rendering aid for the wounded, smiting the faithless, and the will to go on. To add a bit more paladin to the build, simply add the talent rider early in the builds evolution. (Continued below)

The Illusionist (Charlatan, Coyote, or Magician)

This archetype has been around since the early days of D&D. In this build however, I am going to take a possibly controversial approach to the central theme of the what it might actually mean to be an “illusionist”. With this build, we are going to focus on the charlatan, or trickster. As such, it will not be a wielder of powerful magics, but rather a cunning con man looking for a mark.

To begin we start with the question of lineage. Here again, only one seems appropriate for this archetype, a low man. By choosing enchantment, or shapechange as their optional ability, low men can cover a wide range of mythical tricksters. For class, the choice is a bit unusual, a sneak-thief. Again, the intent was not to make a powerful practitioner of the arcane arts, but rather a petty magician. To this end, the sneak-thief is a wonderful choice, especially when paired with the natural abilities of a low man. For a profession, an illusionist might be a cunning urchin, a merchant trader, a traveling entertainer, or a wanted outlaw. The choice is left open to allow a bit of customization.

It is very common for an illusionist, or other charlatans, to choose their talents around what happens when the gig is up and their mark turns sour. Although they are not true spell-casters, some do learn a bit of real magic as they progress.

- Swiftness (basic talent): Any con man will spend a good deal of time in flight. When a con goes wrong, this can help the illusionist flee the scene.

- Knack (standard talent): Some illusionists cultivate unusual skills like chirurgery or alchemy to lend some legitimacy to their cons.

- Legerdemain (standard talent): As low men, illusionists often have access to bits of magical ability. The tricks provided by legerdemain can add some believability to the showy nature of the charlatan.

- Evade (expert talent): When a con goes wrong and the mark wants to string you up, hiding is a fine choice to keep one out of harm’s way.

- Learned (expert talent): The more one knows, the easier it is to pull the wool over the eyes of others. This talent improves the illusionist’s basic knowledge.

- Merchant (expert talent): Many illusionists and charlatans are also sellers of curios and snake oil. Whether conning a populace out of hard earned money, or haggling over the prices of admission to shows, these folk benefit from this talent.

- Natural (expert talent): Though such tricksters are not known for their powerful magics, the ones they do know they tend know well.

- Gifted (mastery talent): This talent must usually be purchased before natural (above), but it provides an illusionist with a single spell. Should the low man possess the ability to enchant, they can create a scroll from which to learn their single spell.

- Watchful (mastery talent): Keeping an eye out for guardsmen and disgruntled marks is much easier when being surprised is impossible.

This illusionist or charlatan is just that, a magical fraud (for the most part). However, the skill set these individuals possess is quite useful for any group of intrepid adventurers or nefarious villains. The ability to manipulate large numbers of people with relative ease is an often overlooked skill. Tricksters of this nature are fairly common in the myths and fairy tales of our collective history. (Continued below)

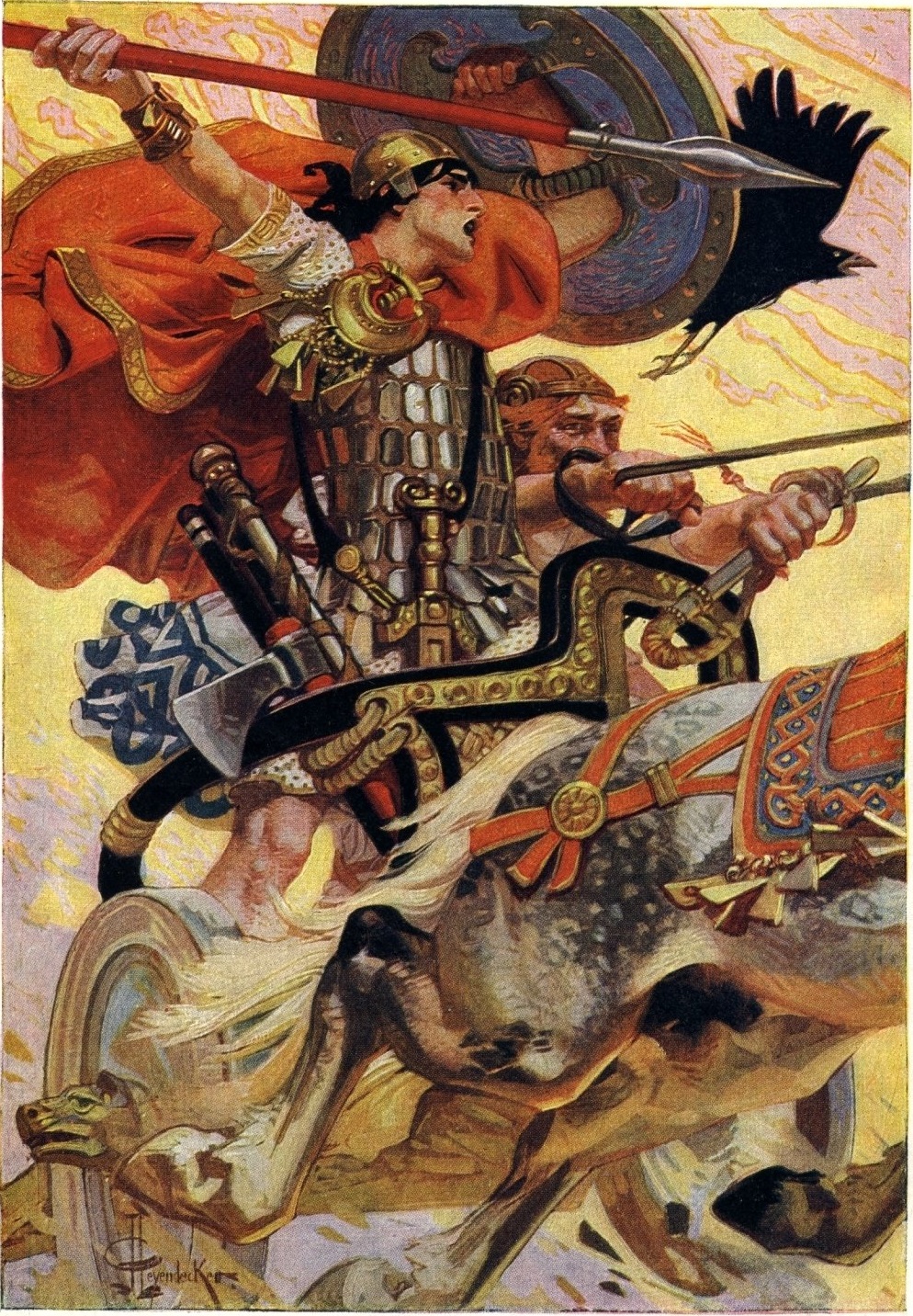

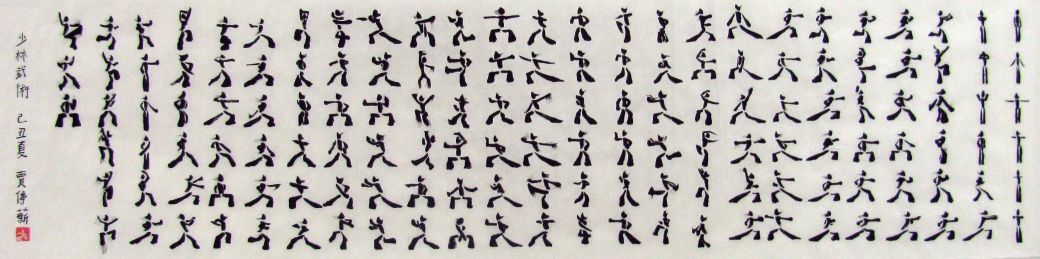

The Monk (Martial Artist, Pugilist, or Wuxia)

The idea of the monk or martial artist also goes back to the early days of TTRPGs and has strong literary roots in the wuxia tales of China. Building this archetype in Faerie Tales & Folklore is quite easy, it just takes a good understanding of the rules and what they contain. This archetype will stretch the bounds of the game a bit, but should work out very nicely.

First, the choice of lineage again leaves one spectacular choice above the rest, a single class high man. The choice of optional ability is more open in this build. Strength can work for the martial artists famed for their inhuman physiques and impervious can work well for the classic “iron shirt” style. However, wirework is likely the most common and thematic of the available options. Class is another relatively easy but surprising choice, magi-user. By virtue, most wuxia tales border on the magical, and some even go to extremes with the supernatural capabilities of their heroes and villains. The magic-user offers such abilities in spades. Profession is also wide open for this build. The monk may come from nearly any background. Now, an important detail is that on page 552 and 553 there are rules for the “qinggong practitioner”. This variation on the single classed high man magic-user is tailor made for the monk, and this build will make use of the option.

The monk’s evolution through talents will generally focus on two things, toughness and the ability to cause mayhem with only one’s fists and feet.

- Pugilist (basic talent): This talent is now acquired as part of being a qinggong practitioner. This change will appear in the coming final release.

- Resistant (basic talent): This talent is a useful option for the “iron shirt” practitioner.

- Swiftness (basic talent): This talent bolsters the abilities of those with the wirework ability.

- Wrestler (basic talent): This talent works well (thematically) with monks who have chosen the strength ability.

- Hardened (standard talent): This talent fits well under the “iron shirt” repertoire.

- Knack (standard talent): Monks often know a bit about medicine and herbalism, this talent can help acquire such skills.

- Stamina (standard talent): This offers a good boost to the monk’s endurance, and allows these martial masters the ability to fight and move for extended periods.

- Warrior (standard talent): This talent opens the door for specializing in one’s fists, no more needs to be said.

- Learned (expert talent): As noted with the cleric (above) a monk is often privy to an education few others experience.

- Tireless (expert talent): This talent furthers the almost inhuman endurance of the monk, allowing them to outlast most foes (earthly or not). This talent is a must for those with the wirework ability.

- Blessed (mastery talent): A must for all styles of hand to hand combatant (especially those with the strength ability), blessed should be purchased twice (the second time is especially useful to finish up the “iron shirt”).

- Specialization (mastery talent): Lethal critical hits with one’s fists (or kicks) is simply par for the course.

- Watchful (mastery talent): The monk archetype is famed for its uncanny perception.

This build is certainly more complex and expansive than most, but so are the tales from which it spawned. An optional talent to further the more D&D inspired monk is to purchase militia and use it to gain berserkr. Any reasonable narrator should allow a player to change the reason for the prohibition of leaving the field of battle from rage, to honor.

It is important to speak briefly about the use of spontaneous magic, as this build is intended to utilize it. In the case of a monk, spontaneous magic is intended to support the characters expanded “qinggong” abilities by using the rules for magic. These abilities are not what would be considered “magical” and are thus not affected by anything disruptive to magic or the otherworldly. The use of spontaneous magic in this situation is intended to be extremely narrow. Such magic should amplify the abilities associated with their school of martial mastery, rather than being a catch all for whatever crazy feats the player has in mind. (Continued below)

The Ranger (An Fhèinne, Huntsman, or Ronin)

The ranger is a classic archetype with a strong following. However, of all the classic TTRPG roles, this one remains the least defined. The woodsman, scout, warrior, and traveler of the wilds seems somewhat of a tabletop jack-of-all-trades, however this archetype is not commonly known for its social skills. In this build, we are going to focus on the highly mobile ranged warrior.

To begin, the archetypes lineage will be a single class high man preferably choosing the abilities of strength or wirework. The class will certainly be that of a fighting-man. Even the profession is a relatively easy choice, skilled ranger. These choices provide a good measure of the classic archetype already. However, with the right investments in talents, we can really bring out the best of this role.

- Swiftness (basic talent): Mobility is paramount for a missile based warrior. This talent offers fine start in improving that mobility.

- Accurate (standard talent): This talent improves missile weapon effectiveness and opens the door for specialization.

- Legerdemain (standard talent): A ranger often knows many tricks that seem to defy natural law: starting fires anywhere, tracking where no tracks seem to exist, and surviving through nearly impossible environments. This talent can account for some measure of that knowledge.

- Militia (standard talent): To get the ranger “feel”, it will be wise to choose archer with the fighter class ability, and mounted archer with this talent.

- Rider (standard talent): Almost every wanderer of the wild can ride, most ride very well.

- Sharpshooter (expert talent): A ranger should have the capacity to perform stunning feats of missile combat. This talent makes such feats much easier.

- Gifted (mastery talent): Many rangers acquire some measure of true magic, though nothing like the magic-user. Even a single spell can radically change the capabilities of a ranger.

- Specialization (mastery talent): This talent makes critical hits much more common.

- Watchful (mastery talent): Not being surprised is quite handy for a missile based combatant.

This version of the ranger fills most of the traditional points: a little magic, a lot of nature, and a heaping pile of raining doom upon the enemy. In addition, they possess the leadership abilities of a fighting-man, making the Robin Hood concept easy to realize. In the end, it makes for a thoughtful warrior with more than a few tricks up their sleeves. This archetype offers a player a bit of everything fantasy has to offer, while being stylistically more grounded than some of the more fantastic archetypes. (Continued below)

The Wizard (Bruja/Brujo, Leech, or Wu/Xi)

The Wizard is the last of the traditional archetypes, and one that shall be followed as closely as possible. Being the learned magic-user, this build will focus on scholarly and magical pursuits. Most earthly cultures have their myths of the speakers to spirits, healers, or curse throwers, the lot of them shall be distilled here for simplicity. The wizard is such a defined archetype, older, strange, oddly dressed, and prone to blather. These beings become forces of nature in the fullness of time and experience.

The lineage of a wizard truly has only a single option (yes, again), and that would be the low man who possesses the enchantment ability. This provides the ever important ability to create items of magical ability as well as write scrolls to pass on magical knowledge. Of course, the magic-user is the obvious only answer to the question of class, and this truly needs little explanation. As to profession, there are several standouts: animal breeder is useful for wizards who fancy wildlife; the landed noble offers a wizard legal cover and the resources to explore magic to the fullest; traveling entertainer provides a fine reason for the wizard to be itinerant; while wanted outlaw may show them to be of the darker variety of spell caster.

This wizardly build will focus on the accumulation of magical ability and scholastic knowledge. The choices of talents should reflect this pursuit.

- Resistant (basic talent): A wizard is more accustomed to the perils of the elements and of the things which bump in the night.

- Knack (standard talent): Most wizards cultivate an odd array of unusual skills, such as: alchemy, chirurgery, herbalism, tinkering, etc.

- Legerdemain (standard talent): This provides a spell based wizard the ability to play with spontaneous magic a bit. It offers the caster a slew of tricks to make their lives seem more magical.

- Stamina (standard talent): Casting spells can be tiring, this talent gives the wizard a bit more room before fatigue sets in.

- Learned (expert talent): If knowledge is power, the wizard is king.

- Natural (expert talent): The ability to cast a spell instantaneously and without a role is a benefit that cannot be ignored.

- Tireless (expert talent): Again, casting spells is a tiring process.

- Ageless (mastery talent): Yes, a wizard needs this talent.

- Gifted (mastery talent): Magic-users do not receive too many spells, access to another one is invaluable.

This wizard feels right at home filling its classic role. It has a substantial amount of magical power, a strong background in knowledge and understanding, as well as a bit more in the tank to keep them going when it is most important. To give this build a bit more of a practical feel, take the talent Merchant early on to create a hedge wizard, or traveling curio dealer. This option works well with the profession of merchant trader, creating a worldly wizard of uncommon practicality and mystery.

This list includes most, if not all of the class options drawn from the first couple of editions of D&D and how to recreate them in Faerie Tales & Folklore. While creating these builds, I did focus on how each should be presented within the framework of the Mythological Earth. This ethic, seen throughout the game itself, steered me toward the “low magic” cleric and illusionist builds, as well as the well rounded ranger. As a game, Faerie Tales & Folklore was designed to allow a high degree of customizability while still maintaining the tenants of the implied setting. Offering simple ways to modify a character or villain, allows narrators and player’s tools to feel more connected with their characters… Because they built them.

Talents are to characters and villains what themes and plot points are to settings and campaigns. They are additional tools that can be used as they are needed. A great deal of the rules within Faerie Tales & Folklore are just that, an expanded tool kit to deliver a certain flavor of historical fantasy. Though many of the rules are difficult, if not impossible, to ignore without breaking the setting, many others can be used or set aside as needed to tell the tale being told. That said, look for a few more talents to be added to the final publication of the game. There are a few holes that still need to be filled in the “customization of class” concept.

As I find myself saying when this point of an article arrives, I hope to have provided a modicum of inspiration and information by which one can better craft their ideas into effective gaming creations. This was a fun exercise, one that I needed to undertake for a good while now, and I hope it is well received. Enjoy your time at the game table friends. Be well…

The Narrative Power of Emotion and Social Connection

One issue I have encountered with some regularity in my discussions with narrators and game masters is how to keep a group of adventures “on task” during a heavily prewritten session or full campaign. Most of the conversations tend to revolve around the idea that pure force is the least desirable, but often only the effective way to ensure the adherence to a prepared storyline. During my time as a game master, I began to steal a ideas from myth and literature which can be invaluable to solving this dilemma. In the following few paragraphs I will outline these tools, how they have been incorporated into the rules of Faerie Tales & Folklore, and how a narrator can implement them within their own games. Now, I must preface this article by saying that some of these suggestions are designed to cause an emotion reaction, and thus should be used with a measure of respect for your current players, good taste, and a lack of being abusive.

To begin, I am going to talk about a common roleplaying trope known colloquially as the murder hobo and what creates this phenomenon. A murder hobo is a character who only seems to exist to travel around a map, kill anything they encounter, and loot the corpses. This is a concept that works well in certain types of situations, such as procedurally generated sandbox style games. However, this process can quickly grow old for players who seek a more epic, or “living” campaign. In my opinion, one of the primary reasons characters easily fall into the role of murder hobos is many character creation systems, especially old school ones, end with a character being an “island unto themselves”. When a character is played who has no attachments or connections to the community or world around them, they will tend to behave in unrealistic ways. Thus, a murder hobo is often the byproduct. If that was the desire from the beginning, then that character creation system has filled a need with efficiency. But, what if the narrator and players are looking for a more story based method of play? What can be done to guide players away from this simple and sometimes mindless format of hunt, kill, loot? (Continued below)

The best answers to this question begin with the creation of a character. When a character exits a game’s creation system complete with a family, friends, a home and possibly even a business, it is more likely that said character will have something the player might feel is worth protecting. By the same token, if said character exits that system with both virtues and vices, the referee has a simple map by which to exploit the character’s peculiarities in ways that are beneficial to creating an engaging narrative. Examples of how these traits can be exploited are listed below.

If a character has a business running an inn and the narrator is trying to persuade the group to go after a local gang of organized criminals, the narrator should try extortion, or the classic protection racket, by having the guild pursue that character and their inn through violence in search of goods, services, or coin.

If a player has created a chivalrous (virtue) knight and the narrator is having difficulty with getting the group to venture to a neighboring land to face rumors of a dragon, simply have the dragon abduct a local noblewoman.

Maybe a drunken (vice) mercenary warrior would like to do something other then face the band of brigands that is harassing a village for free. Simply have the brigands humiliate the warrior while he is too drunk to effectively defend himself.

Finally, If a referee wishes to start a storyline about local children disappearing, have one or more said children be those of the character’s themselves.

It is important in most of these situations, especially ones with consequences that directly impact the characters, to maintain the possibility of being resolved in a manner that does not permanently impact the character. Otherwise, the players simply end up angry and they may lose interest in the current game. As a narrator, one is often expected to be the villain, but taking this role too seriously is almost never a good idea from the stand point of pure entertainment. Keep in mind, most people do prefer a happy ending and some potential endings to a storyline can completely end a player’s enjoyment of the adventure or campaign itself. This is never a good resolution for the player or the narrator.

Many of the points spoken of above are built into the various character creation systems presented in Faerie Tales & Folklore. Specifically, “The Random Lives of People” (page 79 through 90) contains ways to generate family, friends, rivals, and defining events, along with the more universal systems of profession, virtues and vices. Even the introduction line of a character can be used to pull on a character’s emotions or sense of duty when the referee needs to redirect a group toward a predefined goal.

A samurai can be compelled to follow a foolish noble boy, even when that boy causes undue problems for said samurai. To go against this would most certainly be a death sentence for the samurai in question. This social convention can be used to draw said samurai into all manner of tense, if not downright foolish situations.

A dvergr (low man) enchanter could be compelled to seek an ancient horde guarded by all manner of deathless creatures just to expand their knowledge of enchantments and magical formulae (spells). The desire for such knowledge and the lure the treasures that provide it would pull at the very fiber of the character’s being.

The defining event “Successful Gambler” can be used to compel a character who rolled it to gamble when they know the stakes might be too high, such as in a game with the wrong type of folks. Doing so might get them into all manner of trouble, including situations like losing their business, or perhaps even their freedom. Just because they were successful in the past, does not mean they always will be. Eventually, luck runs dry for everyone.

There are no hard and fast rules to force a player into making their character take a certain course of action, as maintaining a strong sense of player agency is important in roleplaying. It is however beneficial for the character to follow these guidelines. “Story Benefits” (page 75 through 77) offer an incentive for players to have their character’s act in accordance with how they are described. Beyond this, a narrator is free to find creative ways within the storyline to aid in the enforcement of a character’s description. (Continued below)

For example, the samurai from the example above might be expected to commit seppuku for acting dishonorably and ignoring the orders of their lord. If this was not done, they would be forced into becoming a ronin.

The chivalrous knight previously discussed could be stripped of their title and rank if they do not heed a call to battle by their king.

A referee should always allow the possibility for the character to redeem themselves, as a player often creates a character with a destiny in mind for that character. Even when such a redemption would be unlikely in the real world, it is imperative that such a possibility be extended. Otherwise a player will be even less likely to respond to being steered by the narrator and their character’s description in the future. When this happens, the referee is likely to lose a powerful tool in maintaining control of the narrative.

The benefit of the systems presented in Faerie Tales & Folklore is that they do not require the creation and penning of a deep, complex background. Rather they exist as notes with which a player can expand upon during a game. If a character is married, do not have the player write the story of how they met, have them tell it during the game. If they were that “successful gambler”, have them tell the story of their success during a night of drunken blather at the inn. These hooks offer grand narrative possibility not only for the player acting as the narrator, but for the player themselves. As a narrator try to convince your players that leaving these hooks open to explore within the game can be of greater use if explored during the game, then when written out prior to the game’s beginning. In many instances, a large, pre-composed background is just a waste of a large number of great narrative possibilities. (Continued below)

The act of “old school” roleplaying needn’t be a dry and statistical affair, though there is nothing wrong with such an approach. A narrator should never need to simply demand their players take a particular course of action, as there are almost always better ways to guide players down the path the narrator has chosen. With but a few simple tools brought in during character creation, a whole myriad of options becomes available for a clever narrator. With a creative player, those same tools can be used to more organically evolve their character in ways dice rolls and statistics never could.

As a narrator, never underestimate the power of creating an emotional reaction. It is a powerful tool in manipulating the players. Nor should a narrator underestimate social consequence, for it is equally powerful in achieving those same ends. Without the hooks necessary however, neither tool can be used with any efficiency. As a narrator, it is vital to maintain one’s knowledge of the people that populate your world, and this includes the characters who belong to the players. Learn about them and what makes them tick. Find things within who they are and how they are presented that you can use to craft better storylines. Don’t just learn about the characters for the sake of manipulation. Learn about them and the vision their players have for them and use what you have learned to help them attain this vision. Learn about them to help provide the player with the greatest possible experience they could have along the way. In that, the narrator becomes more then a game master, they become a storyteller.

When you sit down at the game table remember, those who are gathered with you are in this together… Enjoy the ride.

I’ve a Feeling We’re Not in Kansas Anymore

A certain desire to “hack” the game seems to exist in almost every player and DM I have ever known. I think it might have to do with one’s imagination being sparked, but others may have their own ideas about the phenomenon. When I began developing Faerie Tales & Folklore, along with its pseudo setting, I had this desire to create the most open of an environment as possible. I hoped to pen a set of rules that allowed players to take the basic building blocks provided and run with the possibilities found within the game. In this blog, I aim to have a little fun by detailing how the game’s many modular bits can be used to create a wide array of unusual, if not amusing settings.

Faerie Tales & Folklore has decidedly literary roots to its implied setting. To accommodate this, I devised a few simple subsystems that aid in maintaining this feel. One of the most useful is the idea of optional “plot points and themes”. With these tiny bits and modular rules, one can quickly modify the game to fit any era from the Stone Age to the early 20th century, while adventuring through settings as diverse as the alien worlds seen in the Alethe Diegemata and the otherworldly realms found in the Poetic Edda or the Divina Commedia. Below is a list of fun and often strange ideas for settings, or whole campaigns, to use in your Faerie Tales & Folklore game. (Continued below)

1. The Mead Hall of Valhöll

So… You want a game with more of a high fantasy feel? Try setting a game within the Odin’s mead hall in Valhöll, or Valhalla. The most important rules to focus on here are those of the lower realms of the Otherworld. In this setting, nothing dies permanently, this allows the players to get very rowdy, if such an experience is desired. Technically, all the players will be considered dead, this can be both true (thus useful in situations of a TPK) or simply the mystery of the current campaign, as in “How did we get here and why are we here?”

The plot point “Unbelievable Stories” (page 604) becomes a lot of fun in this setting as telling tall tales while drinking mead in Odin’s hall just sounds like a bang up idea for one crazed set of misadventures. Other good plot points and themes to use are:

- “The Greater the Risk” (page 565), this adds an extra incentive for players to get exceedingly brave.

- “Sporting Events or Games” (page 560), this provides a little non-combative fun to fill in the holes.

- “The Search for Home” (page 536) and “Wandering the Otherworld” (page 546), are important as they can be used to solve the mystery of how the players arrived in this place (if that is actually a mystery).

- “The Impossible Task” (page 543), This can offer the players a way to remedy there current situation.

This fusion of ideas offers a lot of “meat and potatoes” style blood and guts gaming. It can also be used to create a lot of mystery and truly heroic experiences. With some basic changes to where in the lower realms the players end up, this setting is very useful if the whole party is killed but the group wishes to continue the original tale. (Continued below)

2. Children Vanishing Into The Otherworld

This setting/game idea is best used in more modern campaigns (from the 16th century on) as it is focused around the difficulty of getting adults into the Otherworld. In this setting, players will be searching for lost members of the community (most specifically children), who have been disappearing at an alarming rate. Concepts such as the mundane versus the otherworldly will play a central role in such narratives. As is common within the settings of Faerie Tales & Folklore, one of the primary issues a group must contend with is how they are to cross the veil (often repeatedly). This type of tale can also be turned on its head and played from the point of view of the children who are either hiding from the reality of their lives in the mundane world, or are being held prisoner by some villain of an otherworldly nature.

The central plot point here is “The Innocence of Youth” (page 580) as well as the rules found under the heading “Intoxication, Near Death, & The Veil” (page 289). In fact, all of the rules pertaining to the crossing of the veil are very important to such games. Other plot points and themes that benefit such narratives are as follows:

- “The Curse of Geas” (page 536), using such an idea as why the children are disappearing offers a tasty mystery to hook the players into a larger tale.

- “Changeling & Shapeshifting” (page 543), the use of the classic changeling as the antagonist can by a very effective surprise twist when the group slowly uncovers who is behind the kidnappings.

- “Waining Wonder” (page 563), this is important for all games set within later eras.

- “Dust” (page 577), this can offer another way to cross the veil more safely, and procuring some is an adventure in itself.

- “Bad Form” (page 580), this offers a way to keep a game more child friendly, which is useful for versions of this tale where children are playing the children trying to escape (or possibly not be caught by the adults).

- “Weird Science” (page 601), this plot point offers yet another possible explanation for how the children are crossing the veil and who might be behind the whole mess.

- “The Unseen Enemy” (page 603), this is a wonderfully fun plot point to drop into the mystery of why the children are vanishing… Who among the townsfolk is ferrying the children across the veil and why?

This narrative idea works well for an ongoing game as it pulls on most everyone’s basic emotions. Either taken from the viewpoint of children escaping the real world for the wonder of the magical, or adults seeking an otherworldly foe who is kidnapping children within their community, this premise offers all the biggies: fear, wonder, mystery, and all the strange of youthful imagination. (Continued below)

3. The Frozen Earth

This marks a truly alternate setting by using the rules of Faerie Tales & Folklore to simulate life within the era of the last Ice Age. Depending upon how limited, or close to reality you choose to make this alternate setting, it could be teeming with mythic beats and all manner of spirit, or of a highly reduced variety of such threats. The later idea might confine encounters to other men, animals (including great beasts of a more animal nature: dire beasts, etc), and little else. In games of this type, the rules for “Obsidian & Stone Weapons” (page 557) and “Hazards of the World” (pages 277 through 279) become crucial in maintaining the feel of this era. At this point in history, the veil would be at its weakest. The mundane world and the otherworldly are very close during this time and the lack of large concentrations of common men keeps travel to the border realms relatively easy at any time. Other plot points that can prove effective during this setting are:

- “The Search for Home” (page 536), this provides a good survival style theme for a whole clan of early men in a struggle to find a worthy home.

- “The Impossible Task” (page 543), this concept can work with “The Search for Home” (above) to create a truly epic feel in bringing one’s people to some form of “promised land”.

- “Failure” (page 551), is a good tool to balance the search of some aforementioned “promised land”, possibly requiring the group to find a more realistic solution.

- “Heroic Sacrifice” (page 556), in any survival based game the idea of a heroic sacrifice becomes a staple of good narrative.

- “Bloodline of Renown” (page 559), seeing that religion was just as primitive as the cultures of early man, ancestor warship was common, making this plot point very poignant.

- “The Unseen Enemy” (page 603), this plot point is always useful in survival settings, be it a plague or a conflict of leadership, it can add just the right amount of tension.

A campaign set during this period offers great ways to set up the beginnings of the great conflict of Faerie Tales & Folklore, the mundane versus the otherworldly. By playing off both a sense of wonder and fear, it should be relatively easy to set up the roots of the conflict in a natural feeling way. Even the differences in the lineages may be enough to prompt deep suspicion and xenophobia. If a narrator wants to add some horror to the campaign, try adding a “contagion zombi” (page 450) to the scene, be it animal or man. This addition can create a very tense, campaign where trust is a commodity most cannot afford. (Continued below)

4. Death by Dream, or The Sandman Murders

An often told tale that fits well in early modern campaigns is that of a killer capable of murder through one’s dreams. This is primarily accomplished through the use of the spell “dream” (page 107) which remains on the list of allowable spells when using the theme “Magic in the Modern Age” (page 574). As much of the otherworldly narrative will occur in the dreaming realms, all of the available rules for the realm of dreams should be kept close. In this type of narrative, the rules modifications provided in the major literary work “Dracula, 1897 CE” (page 567 through 576) are very useful. The players might be officers of the law and/or spiritualists looking to catch the otherworldly murderer. This narrative can be quite fun, as it blends the possibility of full blown high fantasy tucked away in a very low fantasy world. Horror, crime drama, and mystery may be included depending on the desired tone. Other useful plot points or themes for this bit of storytelling are:

- “Ally From Enemy” (page 533), this provides an interesting way to introduce players later in the tale by having them undertake the roll of a previous antagonist or by introducing a character is an antagonist in the beginning (such as an skeptical officer of the law).

- “Revenge” (page 551) perhaps the killers motivation is just this simple.

- “Waining Wonder” (page 563), is a consideration due to the time frame.

- “Weird Science” (page 601) offers an additional possibility of how the killer might be entering the dreaming realms.

- “The Reality of Insanity” (page 602), this plot point can be a result of, or the actual source of the killer in action (or perhaps it is just people losing their minds). In any event, this concept adds to the sense of confusion and distrust of one’s self within this type of campaign.

- “The Unseen Enemy” (page 603), the use of a modified version of this plot point in this scenario is almost a given.

By switching the setting to a sanitarium and things can get really interesting. Again, through the use of the rules for “The Reality of Insanity” (page 602), the narrative can become truly twisted. With enough patients suffering madness, the sanitarium could become an “Otherworldly Bridge” (page 524). In this variation, a narrator can really bring a sense of high fantasy and horror to a modern environment by utilizing the dream realms in combination with insanity. The characters could even be made patients within the sanitarium, adding the rules of being a “Heroic Outlaw” (page 555) and the reality of not being believed by any “sane” person. In such instances, “The Search for Home” (page 536) could be used to simulate the trip back to sanity (or from the Otherworld back to the mundane) as the mystery of the killer is slowly revealed. (Continued below)

5. Let’s Go Full Metal Wuxia

The Faerie Tales & Folklore system can also be tweaked to accommodate the classic wuxia style narrative. If a tale of this sort is desired, two of the most important rules to become familiar with are “Unarmed Combat” (page 355) and the qinggong practitioner presented in the literary work of “Shui Hu Zhuan, 1110 CE” under the heading of “Magic & Miracles”. From this base, a large number of additional rules become valuable. By mixing various parts of spell casting, spontaneous casting, and hybrid casters, a wide range of martial arts stylings can be achieved. The high man ability of “wirework” (page 33) is particularly useful for wuxia styles (qinggong powered leaps, etc.), as is “impervious” (page 30) for iron shirt type effects, and defining events such as “renowned drunken pugilist” (page 85) can further help realize many of the wuxia tropes. Spells can be used to imitate Taoist talismans and spontaneous magic can fill in most of the remaining gaps (including ideas such as dim mak or dianxue). If you happen to need an animated suit of sentient armor, just have a spirit possess an automaton. There are a few other plot points and themes to consider for a wuxia type narrative:

- “Ally From Enemy” (page 533), this is a common narrative in many martial arts films and stories.

- “The Heroic Challenge” (page 533), another common plot point, “find and beat the five masters” as an example.

- “Unbelievable Stories” (page 604), can offer a sense of braggadocio such characters tend to display and this same rule can be used to play fights out in the minds of potential combatants (a somewhat reoccurring theme in wuxia).

The era in which the tale is being told will obviously change a lot about the setting, though it is important to know that wuxia/martial arts abilities are not affected by “Waining Wonder” (page 563), or any of the other rules that curtail magical effects.

6. The Eternal Champions

This idea was used during the writing of Faerie Tales & Folklore. It is based around the concept that the characters are reincarnating heroes who return every so often to face some great threat to both the mundane and otherworldly realms. During testing, each player choose one of the literary works toward the end of the tome as the setting for the story they were to tell. As the campaign progressed, the players would take turns acting as the referee, thus also switching the very setting and era of the story. Under this model, nearly every aspect of the rules, as well as all the available plot points and themes will be utilized at some point. For the sake of simplicity during the game the following ideas were implemented by all the players involved:

- When a character, or villain, gained a level, that level applied to all the various settings run by each of the players. This prevents a large amount of unnecessary bookkeeping and aids in speeding up each transition. It later came to be decided that, for the purpose of explanation, that a character’s thread of fate worked both ways through time and space. Thus that which affects the past, also affects the future and vise versa.

- Each player kept a modified version of their character that took into account the various modifications for each era and setting. Once the initial work was done, this allowed the players to quickly alternate between the settings when a new player took over as the game’s narrator.

- In this type of campaign, it is a good idea for all the players (and thus the narrators) to be somewhat on the “same page” as to the overall arc of the story. Each player is of course allowed to develop their own plot lines, etc. but the greater story should have some form of unifying thread. Examples of such threads are: an organization of evil that extends through the ages, a rogue defied spirit bent on causing harm to the mundane world, or perhaps an artifact that controls the very flow of time itself being used to nefarious ends.

- It is a good idea for each character, and villain, created to be, in some plausible way, a member of each setting the game will occur within. While limiting, this creates a sense of believability that is important to the greater storyline. For example, if a player wishes to create a Celt from the British Isles, it is a good idea for such a heredity to exist within the other settings (even if the connections are strained).

A campaign using this concept is the most universal of the ideas presented herein and as such, defining individual plot points and themes is essentially moot. The entirety of the game’s rule structure, including any optional rules are likely to be used at some point in the game’s evolution (hence its use during play testing). This style of game is great for a group who either cannot decide on a single setting, or one that enjoys a wide range of potential experiences under the roof of a single campaign.

I hope this has been an amusing look at the potential breadth of settings available within the Faerie Tales & Folklore system, along with how one may use the rules to achieve a desired setting. As can be seen, the existing rules provide an extensive set of possibilities within the pages of one, albeit large, book. In truth, this article only scratches the surface of what is possible with a creative narrator. It has been my intent here to act merely as a spark for others to build upon, to create a set of rules that simply allowed a game’s narrator to realize the types of stories that inspired them and their players. If you find other interesting settings within which to conduct your own games, please tell me about them in the comments.

Go out to your own game tables and challenge expectation. Keep your players guessing and foster a sense of wonder. Above, all enjoy the full expanse of the imagination, it is possibly our greatest tool.

No True OSR (or How to Make Enemies and Anger Friends)

One topic which comes up repeatedly within certain elements of the roleplaying world is the nature of the OSR. What is it, what defines it, and what does or does not belong under this often difficult to define banner? Over the course of this article, I tread into this quagmire in the hope of shedding some light on this potentially polarizing topic. Within the following paragraphs, I aim to show that the definition of the OSR may not be as difficult to pin down as one might be led to believe. However, this definition is not likely to be as satisfying as some may hope.

Before we begin the analysis of what might place a given game or gaming product within the OSR, let us first look at an informal fallacy commonly known as “No True Scotsman”, and why it is important to this discussion. More appropriately known as “The Appeal to Purity”, the “No True Scotsman” fallacy seeks to protect a generalization from contrary examples by changing the definition to exclude the contrary example. This is often done without any reference to an existing objective rule or accepted idea to support the refutation of the contrary example. The example offered in Wikipedia reads thusly:

Person A: “No true Scotsman puts sugar on his porridge.”

Person B: “My uncle Angus is a Scotsman and he puts sugar on his porridge”

Person A: “But no TRUE Scotsman puts sugar on his porridge”

In the above example, person A, when presented with a contrary example, has “shifted the goal posts” to allow their original statement to remain correct. No evidence, nor rule is provided to support person A’s modified claim, they just simply attempted to protect the original generalization by subjectively altering their interpretation of said generalization. Ok, so how does this relate to the OSR? Well, I am glad I asked. Let’s dive into those murky waters and try to avoid drowning under the swell of this much debated topic. (Continued below)

Many of the professed markers others use to identify the OSR readily fall under this “Appeal to Purity”, and it is this fact that I believe causes much of the confusion in identifying what the OSR actually is. In the effort to untangle this strangely subjective title, I will look at many of these identifiers and discuss why they exist more within the realm of an “Appeal to Purity” rather then being legitimate hallmarks of the OSR.

One of the most commonly promoted concepts I hear as an identifier of the OSR is the phrase “Rulings not Rules”. An interesting, and admittedly old feeling idea no doubt, but is this the core of the OSR? Though the idea certainly exists in older games, I believe some measure of this is vital to the idea of roleplaying itself. Considering that roleplaying is a form of structured, cooperative imagining, it is important to have a certain amount of flexibility in how the myriad of situations can be handled. Conversely, this would mean that any game that promotes a flexible take on its rules has a claim to being a portion of the OSR. The Fate system utilizes this very idea to the extreme, as it promotes vast levels of hacking its system. Fate also promotes an often ambiguous “let the game master decide” type approach to many of the game’s vital aspects (see what I did there?). However, even in the most well intended efforts, Fate seems to fall short in its attempts at feeling “old school” (Fate Freeport comes to mind). Lastly, “Rulings not Rules” reeks of an “Appeal to Purity” as the idea is actually both common and somewhat undefined. As such, it can be applied or withheld at the whim of the user.

In the end, is the idea of “Rulings not Rules” important to the OSR? Yes, but it shares that importance with a great number of non-OSR games. Thus, it cannot really be a defining feature, as it borders on some level of ubiquity within roleplaying world, The prevalence of the crowd favorite “Rule Zero” and its application to gaming in general goes a long way to proving this point.

The next concept I hear regularly as a possible defining feature of the OSR is “Less Plot, More Player Agency”. This one is interesting, though not really because of its merits as a defining feature of the OSR, but rather because it is more of an approach to how any given group chooses to play the game. Similar to the “Ruling not Rules” concept above, the idea of “Less Plot, More Player Agency” is in no way specific to the OSR. Many games take the approach of a strong sense of player agency without feeling remotely part of the OSR (again Fate comes to mind here). However, this is no doubt a facet of what seems to make up basis of the OSR. Though I would argue that this fact is driven as much by the type of player and game master that are common purveyors of the OSR, then the rules themselves. So again, we arrive at the “Appeal to Purity”, as this potential feature is not so much a facet of the rules as it is those who use the rules.

Another idea I hear a good deal about is “Equipment is the Original Skill List”. Now this one, as strange as it may seem, warrants a good examination, but not for the reasons one might first assume. While it is true that many early roleplaying systems did not make use of long skill lists, or even much in the way of skill mechanics, that is not the real reason this concept is so interesting. When a fan of the OSR says “Equipment is the Original Skill List”, they are actually saying something else they might not know they are saying. This idea of equipment defining what a character is capable of doing is based upon a strange but very interesting portion of many truly “old school” roleplaying games. It is built on the assumption that a character knows everything the player knows regardless of what the character would actually know based upon who they are. This is the original meta-gaming, and it is because of this idea that many fans of “old school” games feel as though they are being challenged more directly by the experiences within the game. Thus, the sense of “intellectual accomplishment” is much greater. In such systems one does not simply roll one check to find a trap and another to disarm it, one must actually use their wits and knowledge to find and disarm the trap. It is here that I believe a good deal of what we might consider the OSR comes from, the sense of being personally challenged by the game itself. This is an element commonly overlooked by modern games, and though complex skill mechanics go a long way toward keeping players on a level field, such mechanics reduce the feeling of being directly challenged by the situations encountered during any given narrative.

However, is this the core of the OSR? Is this the heart of the elusive beast? I am again inclined to say no. The reason is again simple, there are games without complex skill sets and mechanics, that rely heavily on player meta-gaming which in no way feel like part of the OSR. Thus, we are again stuck with something being a feature but not a defining one. Again, this allows the “Appeal to Purity” to be invoked at a whim.

So the rules, it would just have to be the rules right? It would seem that a vast majority of the games that fall under the moniker of the OSR are built around an extremely narrow group of very similar rules. Thus, this concept just has to be the core of the OSR, I mean if not this then what, right? Again, as strange as it may seem, I am inclined to say no. While it is true that a very narrow set of rules has become the basis for a large portion of the OSR, it is equally true that the OSR has pushed beyond those borders and into the wholly unrecognizable. Thus, even the very rules themselves fall to the “Appeal for Purity” too easily.

It must be stated however, that out of all the concepts offered thus far, this one does carry the most weight. If someone starts talking about running a game with: 3d6 six times in order for attributes; races like elf, dwarf, human; classes such as fighter, cleric, magic-user, thief; armor class, hit points, and levels of experience it becomes hard not to feel nostalgic. Even if you were not there in the beginning, most will understand the roots of these ideas to some extent. Just like the I-IV-V progression in music, this will feel “old” in a way the other ideas presented cannot claim.

As a side note, It is my belief that the regular use of nested systems in old school games is an often overlooked feature of what makes a game “old school”. I believe that the oversimplification of a game’s mechanics can lead to a sense of mechanical tedium during a session. Most old school titles had a new sub-system for almost everything that could happen within within the game. In my opinion, this is a feature of immeasurable importance. If you are playing a d20 centric game and your game master tells you to roll a d% out of the blue, you have no idea what is going on! That uncertainty adds to the emotional impact of the situation, and can completely change the vibe at the game table. (Continued below)

Back to the matter at hand–

If the rules themselves cannot even be the defining aspect of the OSR, then what is left? How can we put a label on the magic element that provides that warm fuzzy comfort of the much lauded OSR? Well in truth, here is where we come back to the informal fallacy discussed in the beginning of the article. It has become my belief that the whole idea of the OSR is a giant “Appeal to Purity”, a very complex version of “No True Scotsman”. The OSR is, in no uncertain terms, bits of everything spoken of above. Yet, any attempt at a concrete definition is almost guaranteed to be riddled with subjective opinion. Is there a clearly definable set of attributes that is the OSR? No, I do not believe so, but there is an OSR. In my opinion, the OSR is intended to be as mutable as memory. It is a label we can place on a game to indicate it feels a certain way, even if we cannot adequately define what that is. I have come to think of the OSR as another version of “back in the day”. As such, it becomes a euphemism for the way something is remembered as opposed to what it may have truly been.

This look at what the OSR is has not been in vain however, on the contrary, what it has shown is something deeper. What is the OSR? In the most simplistic terms, it is anything that provides a sense of nostalgia and prior understanding for the player. The OSR is, in my opinion, simply an idea or concept that indicates a basic adherence to one or more properties within a game that might appeal to a certain mindset. It is in the fluid nature of one’s relationship with these identifying properties that aids in creating the the “Appeal to Purity” so often seen in the attempts to describe the OSR.

The idea of “old school” is in no way unique to the world of tabletop roleplaying, nor are the endless debates about what constitutes “old school”. In music, the term “old school” is found in hip hop and punk rock (among others) with some regularity, with the title often imparting some quasi-mystical sense of “street cred”. These topics can be both polarizing and alienating, as they often form a sort of elitism behind their application. The connotation that a certain subset of a knowledge base has more validity because more time has passed since its creation or understanding, is actually a bit bizarre but it is none the less a very common ideal within the vastness of human expression. It does serve a purpose however, and that purpose is to offer a “road sign” toward certain portions of the topic at hand. To that end, the idea of the OSR is of near vital importance for those who pay attention to its utterance. It is the weight of expectation behind those initials that speaks to us an a subconscious level. It is here that the true heart of the OSR rests, as it whispers in the ear of those who know, “It’s alright, you will find solace here…”

Enjoy the coming holidays friends! Feast well and remember to avoid unnecessary conflict with family and party members.

A Statement of Inclusion

It has become important for me, in light of many continuing controversies within our hobby, to express my feelings about the topic of equality and inclusion. In the space of these few paragraphs I intend to make my personal thoughts on the matter of misogyny, racism, and other forms of prejudice nice and sparkling clear. If you are the sort who uses the term “social justice warrior” as a derogatory title, you may wish to leave now and not come back. To others who might read this article, I will not be discussing my game Faerie Tales & Folklore to any great length, nor roleplaying games in general. Instead, I aim to focus on the social aspect of our favorite hobby and my disdain for certain subset of those who make up the gaming populace.

Being a member of what is commonly titled “Generation X”, I came to adulthood in the late 80s and early 90s (well mostly the 90s). Furthermore, I was what some at the time labeled a member of the alternative movement. My friends and I stood against the prejudices of social convention, I wore skirts and makeup, surrounded myself with LGBTQ friends who I love dearly, and I did my part to help body modification reach its current level of ubiquity. Those in my close knit but large group of friends faced these challenges within the confines of a strangely conservative small town of Northern California. We were often ridiculed, shunned, and with startling regularity, physically attacked for the simple act of expressing a different view of how we thought the world should be. We had to learn to stand together, we had to learn to fight those who sought to do us harm, and in the end, we helped change minds about what was acceptable.

It was this struggle that came to define me as a human. It shaped every aspect of who I am and even left me with a bit of an unfortunate persecution complex, to which I have only recently been able to move beyond. This struggle was also one of great joy, as we were the witnesses of fear being stripped away from parts of our corner of society. To see friends, once terrified of who they were, walk in broad daylight, proud of their unconventional identities was something truly elevating to behold. We saw a different future for humanity and we sought to hasten its growth. We saw everyone as equal, well except maybe the neo-NAZIs who would plague our lives and attacked us when we were alone. We did not see any as less then others for such things as gender, promiscuity, personal tastes, or the desire to experiment with safe drug use. It was an age of reinvention and of owning one’s own sense of personal identity. It was the continuation of the efforts our parents started in the 60s, and we were the proud standard bearers of a changing culture. (Continued below)

So what exactly does this have to do with gaming you might ask? Well, in recent years I have seen certain elements of our closed minded cultural history fester to the surface in one of the communities I have felt a portion of since I was seven years old, the world of tabletop roleplaying. With the recent controversies coming from White Wolf and the not so subtle issues that permeate the OSR community, I have once again felt the specter of prejudice rise from the darkness of our collective consciousness. I have felt the chill wind of hate blow around the community slowly tainting something I love dearly.

When I set out to write Faerie Tales & Folklore, I wanted to create something that could be true to the history of humanity without embracing the hate of our collective cultural history. I wanted to write a game that embraced multiculturalism, that was not afraid to tackle issues of drug use or atheism, but also felt true to the roots of our history as a species. In short, I tried to simultaneously honor our history while avoiding the potential of insulting others for who they are and what they believe. The game I wrote deals with some dark topics and unfortunate facts about human existence as it was and often still is. I had hoped we could look at some of these issues unflinchingly as reminders of where we have been and how far we have come.

Roleplaying is a social activity and in that space, it has little room for the anti-social ideals of an unfortunate few. As a microcosm of humanity as a whole, roleplaying is best played without prejudice and hate, as these traits steal the very soul of this wonderful hobby, the drawing together of people in the name of collective imagining. Any social activity has the potential to draw people together, but when prejudice and hate are brought to the table, the social nature of roleplaying becomes threatened in a very real way. This bristles the hair on the back of my neck and brings the fight back out of me… That same fight that powered my peers as a youth to challenge the social conventions of the day. It is this sense of purpose that has set me to typing this article you currently read.

As a species, we need to move beyond our petty differences. This is not a passive state, but rather an active pursuit. We cannot be complacent in the face of bigotry and prejudice, nor can we simply ignore it and hope it just goes away. We should all seek to embrace what makes us each unique and in so doing raise our collective selves above our more base natures. The act of roleplaying itself is a remarkable tool for this process and should not be used as a tool of division or social exclusion. We must be better then that. We must be better then the recent controversies of our strange corner of the entertainment industry. As social creatures we are at our best when we are unified… Even when we are at the game table.

Peace friends…

OSR Guide For The Perplexed

In order to “get back in the saddle”, I chose to fill out this little questionnaire going around. It appears as though all the cool grognards are doing it, thus it seemed a reasonable way to get myself back to working on my community after the gut punch of the Google+ issue. To be real however, I look at the idea of the OSR like a lot of old punks look at the idea of old school versus new school punk rock. To paraphrase an old punk friend of mine when he was asked if he was “old or new school”– He simply stated, “Kid, I am out of school.”

I know we as humans tend to enjoy labels, as they offer a sense of comfort through the ability to easily identify what we have encountered. However, a label rarely tells you the truth. A label often hides too much of a things subtly, and it paints in too broad of stokes to be useful to those who truly pay attention. For those who casually encounter a thing, the label just allows one to place the object of inquiry on a shelf of “I sort of know what this is” and leave it there without having to truly understand what sits behind that label. In this, a label fails most everyone.

When I set out to write my own game, I really had little idea of what the OSR even was. I did not set out to make an “old school” game, I simply wanted to make a game that had the feel of some of my favorite elements of roleplaying over the past forty years. It was only after I began to research and test my ideas with others that I encountered the term OSR. In fact, I even spent time arguing that my game was NOT in fact an OSR title. In the end, it seemed that I lost that argument. With that information known, I can imagine many of my answers to the following questions are likely to be quite different then those of other OSR fans and some are likely to seem absolutely daft. That tends to be the nature of expectation and labels, once we look beyond them, things often do not appear as we thought they should have.

So let’s get on with it shall we?

1. One article or blog entry that exemplifies the best of the Old School Renaissance for me: We start off with a really tough one here. Since I am not an avid blog reader, I am not sure I could name a single blog article, let alone one that I felt exemplifies the OSR. However, there was an article (really more of a LONG forum post) on combat in OD&D using the Chainmail rules. It was that article that sent me hurtling through history in the “way back machine” to my earliest days gaming as we tried to figure out the OD&D/Chainmail rules as grade school kids in the late 70s through early 80s. My friends and I had to make due with hand me down books from a friends older brother and those hand me downs were Chainmail and all of the OD&D books. This article cleared up issues we had and acted as a reminder of what was so fantastically cool about my first few sessions of what would become a lifelong obsession for me. When I stumbled on this article, I realized that my ruleset needed to be based around the original rules I used to undertake my first steps into the world of roleplaying. (Edit: The article was on the “odd74.proboards” forum.)

2. My favorite piece of OSR wisdom/advice/snark: If you have time to min/max or character optimize to munchkin land, you are likely not actually playing much.

3. Best OSR module/supplement: Not really a supplement, and possibly not even really a portion of the OSR, but I have to go with all of Beyond the Wall. There is just something about that game and all of its supplemental material that just oozes the wonderment of my favorite fiction from boyhood. The developers and writers of that game truly crafted something magical and I am constantly inspired by the unique approach they took to what is essentially a multi-edition D&D clone.

4. My favorite house rule (by someone else): This one is easy, the game master rolls all the dice during the game and keeps track of all the numbers. The players only know the words behind their characters. No stats, levels, hit points, or anything of that nature are known to the players. This enhances the sense realism of a game (IMHO) by not making such things clear and thus dependable. Though I do not use this idea in Faerie Tales & Folklore, many of my favorite sessions as a player and game master utilized this house rule.

5. How I found out about the OSR: When I began writing my own game, I slowly became aware of the idea of the OSR. At first, I thought it was pure silliness, but later I did come to see some point, albeit small, to making such a distinction.

6. My favorite OSR online resource/toy: In truth, the best online resource for the OSR has been the OSR community on Google+. If it is OSR, it has appeared there at one time or another. The answers to any questions I have had, all the help I have needed, and some of the best people I have encountered online have been found there. Not sure anything else has come close in my experience.

7. Best place to talk to other OSR gamers: I have long found Google+ to be one of the best places to prattle on about the OSR and RPGs in general. Its demise will be difficult for me to move beyond, as I put so much energy into the various communities there.

8. Other places I might be found hanging out talking games: Rarely, my nom de guerre can be found on Reddit, but Mr. Thorne comes out less and less these days.

9. My awesome, pithy OSR take nobody appreciates enough: That ‘Rule Zero’ is an overly lauded idea that really does not maintain the best ideals of a cooperative roleplaying experience. The game master should be respected, but no player at the table should be seen as any more or less valuable then any other.